That’s why, in August 2011, WWF began work on one of the largest, most complex conservation, development, and climate change projects ever launched in Nepal. The program was dubbed Hariyo Ban, short for a Nepali saying that means “Healthy green forests are the wealth of Nepal.”

The five-year, nearly $40 million USAID-funded program brought together WWF, the international development organization CARE, the Federation of Community Forestry Users Nepal, and the National Trust for Nature Conservation. Together, the groups have worked to forge a new model for a landscape-level, community-driven approach to conserving biodiversity that also helps people adapt to climate change and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions by storing carbon.

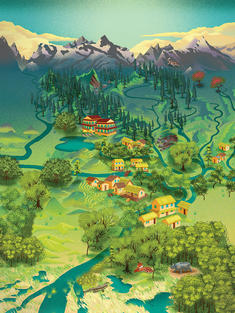

“Hariyo Ban works across two major landscapes: the Chitwan-Annapurna Landscape and the Terai Arc Landscape, which together cover 40% of the country,” says outgoing Hariyo Ban chief of party Judy Oglethorpe. “As climate change advances, we know it’s going to have serious impacts on ecosystems and people, including entire river basins and their freshwater resources. By working at different scales, we can work with upstream and downstream water users at the same time.”

The entire Chitwan-Annapurna landscape, says Ryan Bartlett, WWF’s senior specialist for climate resilience, is vulnerable to climate change. Prior to the launch of Hariyo Ban, researchers at WWF had already begun looking at the specifics of climate resilience, observing individual ecosystems within the Gandaki and other river basins, and studying how each is uniquely affected. A common theme—water—quickly emerged.

Bartlett says, “Sometimes there’s a lack of water and sometimes there’s too much. And sometimes it comes at unexpected times. Unfortunately, those new extremes are undermining people’s lives.

To help people in the Gandaki basin adapt to the changing conditions, Hariyo Ban organized climate vulnerability assessments at various levels—from community to landscape—to identify situation-specific solutions for the people and the land. This led to a strong focus on people’s livelihoods and their ability to prepare for and recover from disasters.

For example, when people suffered from landslides, crop failures, or water sources drying up due to changes in rainfall patterns, Hariyo Ban supported the restoration of forests in their water catchments to stabilize slopes and conserve water supplies. It provided greenhouses (called “plastic tunnels” in Nepal) to diversify crops and incomes. And it provided support to upgrade foot trails to improve local people’s access to harvesting areas and schools, and to promote ecotourism.

“You can’t do good conservation,” says Bartlett, “without learning from the people who live there and helping meet their needs.”

So Hariyo Ban partners spend months, or even years, getting to know the intricacies of each target community—working with people to assess how they and their ecosystems are vulnerable to climate change, helping them develop programs that address specific needs, and helping to secure funding and resources. The process has a special focus on including the voices and concerns of those who are most vulnerable—including women, those with disabilities, and the very poor.

Five years on, and against daunting odds, the program is a striking success. Across both landscapes, hundreds of thousands of people have benefited from Hariyo Ban, and more than 160,000 acres of degraded forest have been improved with the aid of hundreds of locally run user groups and protected area staff.

“The program also worked with thousands of local people and Nepal’s government to mitigate climate change by reducing or sequestering an estimated 3.7 million tons of carbon emissions in Nepal’s forests,” says Netra Sharma, Natural Resources Management and Climate Change Programs Specialist for USAID/Nepal.

Those living in project areas have reported economic improvements, increases in wild species, and the recovery of local forests.

And each community has its own story to tell.