By the numbers: Hariyo Ban

Green recovery and reconstruction

101,380 days of “cash-for-work” employment funded to provide post-earthquake income

22 women-led households receiving economic or other benefits from recovery work

3,810 single women and adolescent girls benefiting from recovery work

17,401 people with increased economic benefits

1,023 participants in green recovery and reconstruction trainings

3 post-disaster assessments and policy documents supported

115 miles of foot trails created, improved, or rebuilt

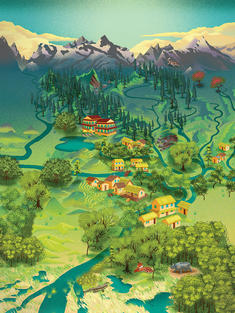

In his village of 900 houses, only a few remained standing after the earthquake. Today, however, the community is the picture of healthy recovery. The houses boast solar lights and are attached to a grid powered by micro-hydro—in essence, water piped from the nearby stream into a shed where it powers a generator. After the earthquake, Hariyo Ban helped the community rebuild it so that schoolchildren could again study in the evenings and adults could go about their work. Livestock and cash-for-work programs have allowed people to start generating income again, and irrigation canals and trail repairs have allowed agriculture to resume. In all instances, Hariyo Ban has guided the community toward eco-friendly rebuilding, to increase resilience and reduce the risk of future disasters.

Immediately after the earthquake hit, Hariyo Ban partners focused on urgent needs, bringing people tarpaulins, blankets, food, and other emergency supplies. They worked with the government to identify recovery needs for the forest and environment sector, and to develop a more detailed rapid environmental assessment that identified potential environmental risks from disaster recovery and reconstruction efforts—and offered ways to mitigate them. Hariyo Ban also helped communities, as well as the housing, water supply, and education sectors, adopt environmentally sound practices.

“Sometimes, the natural rush to build back what was there before is not always best for the community that we’re trying to support,” says Anita van Breda, senior director of environment and disaster management at WWF. “If we’re rebuilding homes, you need timber, sand, gravel, and mortar. All of that has to come from someplace. If we rush in and extract it all at once, we’re probably setting up a different kind of risk to nearby communities and the biodiversity that supports them. If we want to rebuild healthy and productive communities, the environment has to be a part of that.”

Jugbahadar Gurung, a young man from Simjung, couldn’t agree more. Students are going to school again; farmers are beginning to plant. Gurung has replaced his livestock, joined an antipoaching unit, and begun to take an active role in protecting the environment.

“We’re rebuilding,” says Gurung, “through the support of Hariyo Ban.”