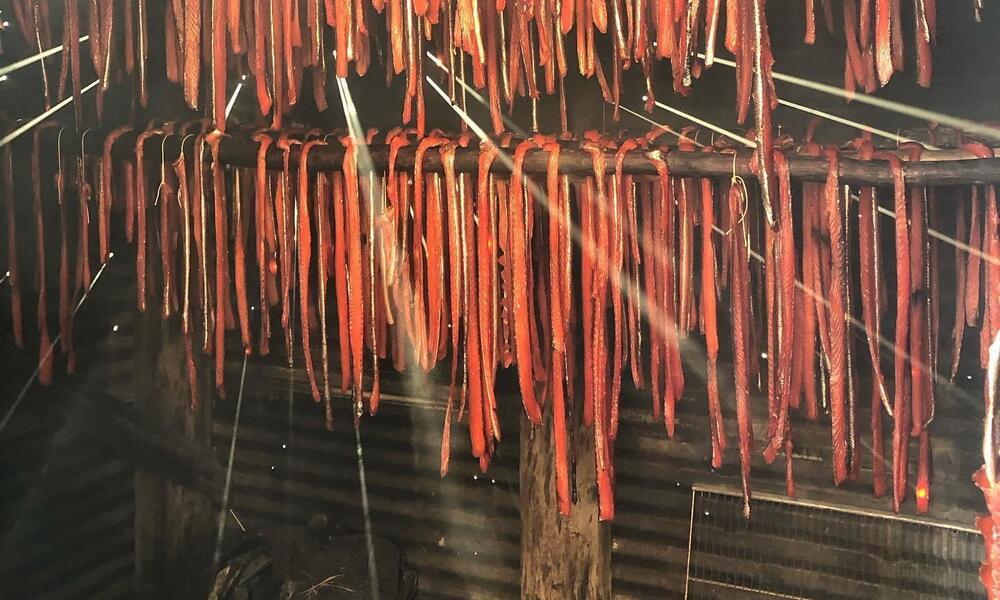

My family has always been eager for the hard work the subsistence way of life entails. Inupiaq survival is based on hunting and gathering practices guided by thousands of years of traditional ecological knowledge that our ancestors learned and passed down through generations. My grandmother is the reason that my family and I carry some of this knowledge today. With love and patience, she has passed down the skills it takes to use and prepare every part of an animal. She taught us not to waste.

In the last few years, my family has struggled to fill our freezers with king salmon as we see fewer and fewer of these fish return to our rivers and streams. Today, the work that once took my grandmother a few days takes us twice as long. The king salmon that we harvest today are younger and smaller, forcing us to put 10 more fish away to equal what we once had.

Warming oceans and the impact on fish populations

The king salmon, dog salmon, and silver salmon populations in the Yukon and Bering Strait are deep declines, likely due, in part, to the rapid temperature increase in oceans and headwaters where they spawn. Not only has this rise in temperature affected the salmon populations but also other marine life. Near St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea lies a cold expanse of water on the Eastern Bering Sea Shelf. The cool water has kept pollock and Pacific cod south of this shelf. But in 2018, the ocean warmed so drastically that the two species of fish had to migrate and feed farther north than normal. Pollock and cod prey on king crab and small fish native to the area north of the Eastern Bering Sea Shelf and their recent encroachment into northern waters has contributed to the crash of the king crab population. Both the king crab and king salmon populations used to sustain a remarkably successful commercial fishing and crabbing industry, as well as supply food to entire communities. A survey conducted in 2006 found that the average amount of subsistence food harvested per household in the Bering Strait region is over 3,700 pounds per year, with 77.5% of the food gathered being from the ocean.¹ Today, this type of harvest is just not possible.

Shipping traffic is on the rise

Rising temperatures and winds are creating another problem for wildlife and people, too: increased shipping.

In recent years, a lack of sea ice due to a warming planet has opened once impassable waters in the Bering Strait—and with it, a drastic increase in shipping. Routes across the Arctic are significantly shorter than those commonly used today. Current data reflect a significant increase in transits observed in the Bering Strait in the last decade. While only 262 transits were recorded in 2009, that number increased to 434 transits in 2019. These vessels often travel through delicate marine habitats and Indigenous hunting grounds, which increases the risk for collisions with hunters and marine mammals. A collision can result in damage or loss of transported goods such as oil and natural gas and a spill would devastate the region. There is little infrastructure available to clean up such a disaster.