Elephant Collaring

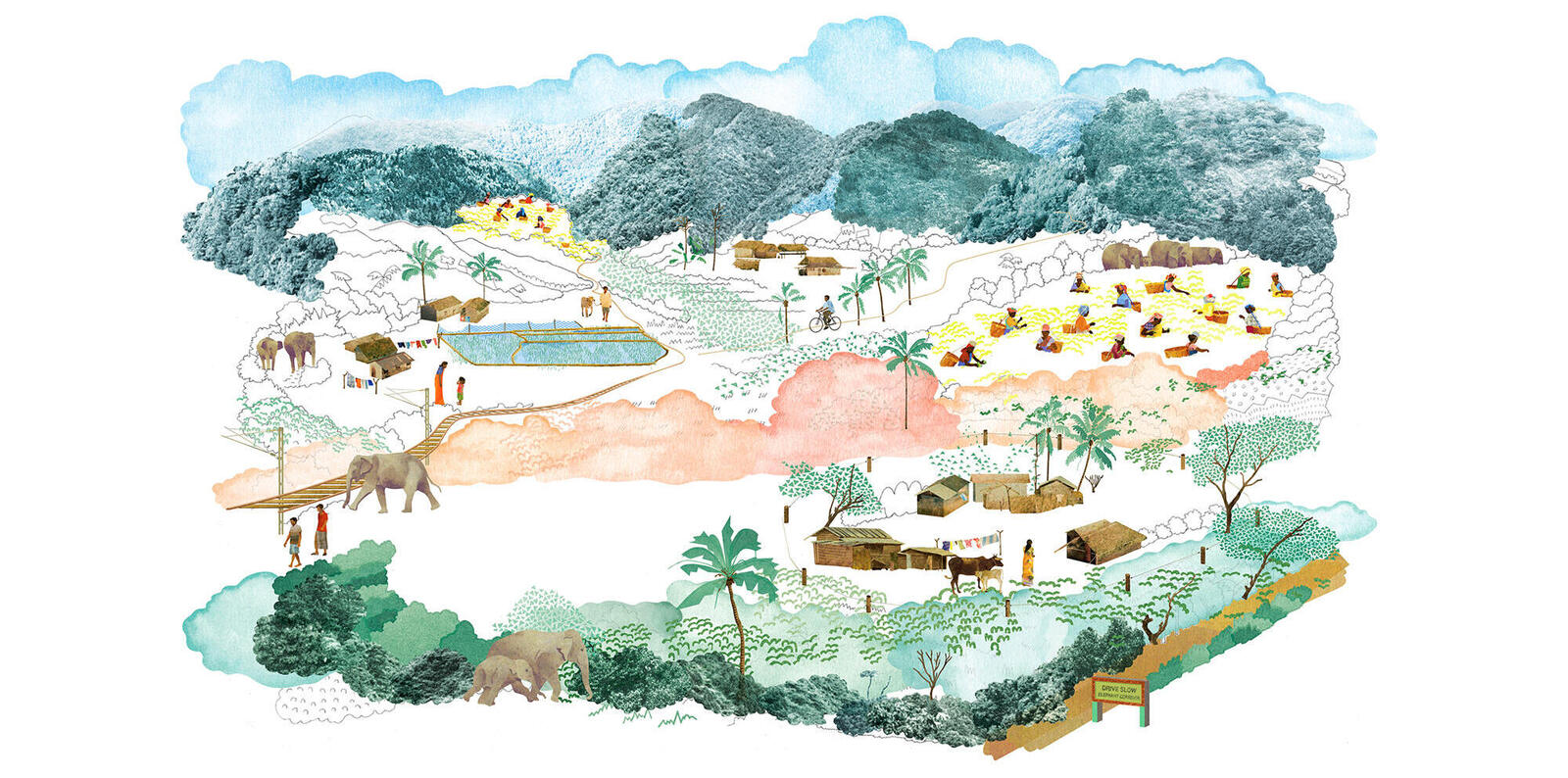

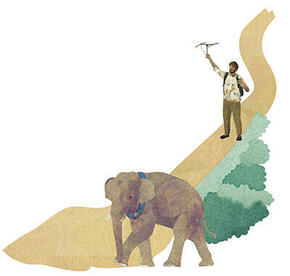

By November 2020, Arjun Kamdar, a wildlife biologist with WWF-India, and his team had spent months scouting elephants that visited the vast, multiple tea gardens in Assam’s Sonitpur district. Their goal was to attach a GPS collar to a select individual in order to collect valuable information on elephant movements. The team of veterinary experts and Assam Forest Department officers was finally able to dart a female. While she was still awake—but tranquilized, her attention deflected by a blindfold—they attached the collar around her neck. Kamdar dubbed her “Tara” after Tarajuli tea garden, where she was collared.

Radio collaring isn’t easy. It takes five to seven people several hours to find and tranquilize an elephant. Kamdar, who is currently monitoring the collared elephant, believes tagging technology is the key to unlocking the mystery of an elephant’s whereabouts during the lean season, when it leaves the harvested fields for parts unknown. “Where are the elephants for nine months?” Kamdar asks. The GPS collar could provide an answer.

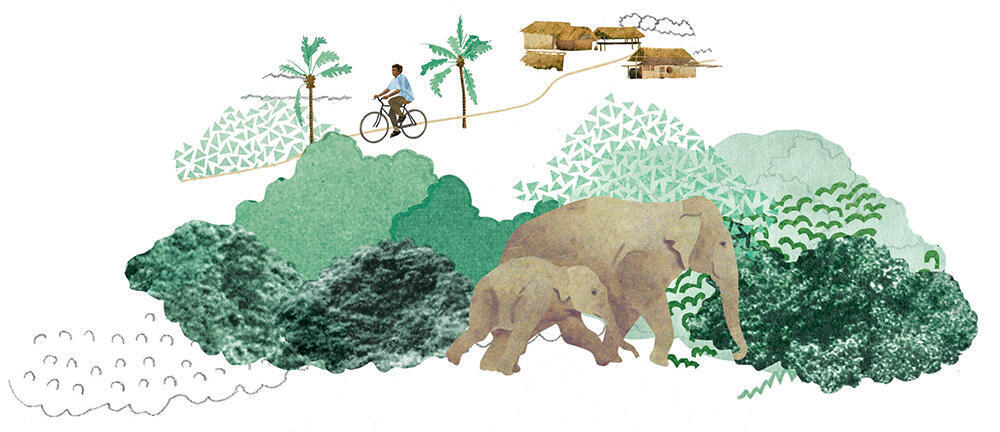

In Sonitpur, WWF-India is hoping to fit five elephants total with GPS-enabled radio collars that can relay more information on what habitats or corridors they prefer, how they travel, and whether environmental changes are altering their migration patterns.

The team also has plans to attach an accelerometer to the collars to understand the activity of an elephant at any given time, whether it’s drinking, sleeping, or walking. According to Hiten Baishya, WWF-India’s coordinator for the Brahmaputra Landscape, mining location-specific data from GPS-tagged animals could help the Forest Department determine where to extend protection across their range. And it could shed light on what elephants are feeding on, helping to determine which types of vegetation need restoration. It could also provide villagers with early warning of elephant presence and help reduce human-elephant conflict.

What if, Baishya and Smith wondered, these fences were replaced with voltage-regulated, nonlethal electric fences powered by solar panels—an inexpensive tool already being used in another WWF landscape? “Sunlight,” explains Smith, “charges the system battery, which produces regulated pulses that run through the wire of the fencing system.” Unlike lethal electric fences, the new fence technology would deter elephants by delivering a brief electric shock that wouldn’t jeopardize their lives.

By 2015, after securing community buy-in, Baishya and Smith helped villagers form a close-knit community response team consisting of affected villagers and provided them the materials and technical guidance to install a solar fence. And since electric fences need regular maintenance to ensure their effectiveness, the villagers and the Forest Department elected Anil Bey as the fence caretaker in 2016. Bey received a portion of the lump sum collected from villagers for the upkeep of the fence until the Forest Department fixed his stipend for this task at 4,000 rupees a month.

The fence, of course, is only as good as its maintenance—a continual task for which Bey was trained through WWF-India. Bey explains that electricity runs through the fence in the evenings during the harvest season—September to January—when elephant break-ins are on the rise, as well as at night during the lean season, when elephants are less likely to raid crops and damage property.

Bey’s quick checks and fixes include lightly pinching the wire with a voltmeter to check the current flow; clearing undergrowth that might touch the wire and drain power; and ensuring the fence components—solar panels, batteries, and energizers—are not defective, damaged, or removed.

His involvement has helped reduce human-elephant conflict, allowing tea garden workers and villagers to live in peace. “There was a time,” he says, “when they wouldn’t stop crying hysterically over elephant encounters.”

Community management of solar fences in Biswanath district led to a 70% reduction in elephant-related damage in the adjacent tea gardens. And there are almost no elephant sightings in the villages anymore. In fact, Anil Baruah almost misses the sense of unity he experienced during the chaotic elephant encounters of the past.

Around 60 miles away, community cohesion over maintaining another 13-mile solar fence remains strong in the eight villages of Sonitpur district, despite incidents of human-elephant conflict coming to a halt in the past two to three years.

Tulsi Upadhyaya, who belongs to one such village, Sonai Miri Gaon, is the head of the Hasti Manab Suraksha Committee—the Elephant and People Protection Committee—overseeing the financial contribution of the villagers toward fence maintenance. “Everyone understands the need for fences in order to live in close proximity with elephants,” he says. “Each household contributes 300–500 rupees into the committee’s coffers at least once in three years. And a reliable resident is voted to guard over the fence.”