Development and infrastructure

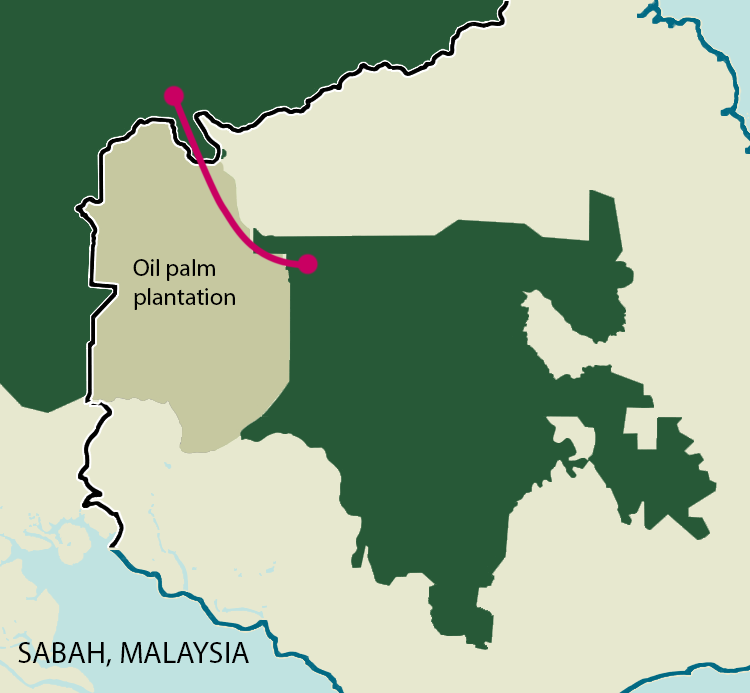

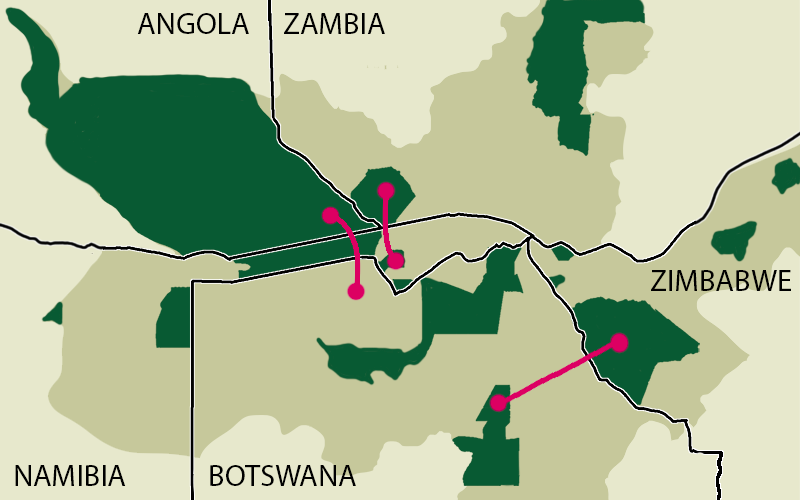

Unfortunately, human activity is disrupting ecological connectivity, often breaking up and degrading habitats in ways that are harmful to the animals that live in them. This can also lead to human-wildlife conflict as people and animals increasingly come into contact with each other as they compete for space and resources.

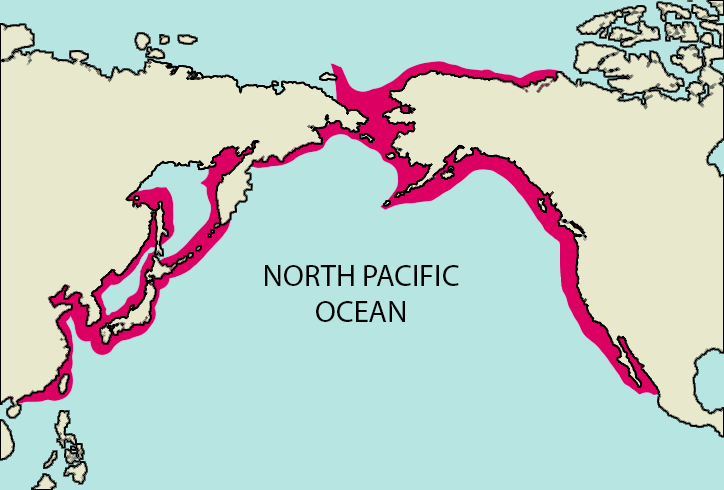

On land, a road or fence may prevent animals from accessing a water source. Expanding cities and towns can encroach on land once rich with wildlife, blocking their movement. In rivers, dams can prevent fish from swimming upstream to breed or find food. Similarly, offspring of marine species often travel great distances in the ocean between the nursery sites where they are born and feeding areas. These habitats can be connected by ocean currents, but when these routes are disrupted by activities such as overfishing or infrastructure development, offspring face difficulty reaching their destinations.

Fishing gear, shipping routes, and associated noise also negatively impact animals like whales that migrate vast distances in our oceans.

Climate crisis

The climate crisis, which is also caused by human activity, is contributing to increasing resource shortages, more frequent and extreme weather events, and rising and warming oceans. Because of these increasing threats, connectivity is more important than ever so that species can adapt and move away from places where conditions are becoming less favorable. Connectivity is crucial for the survival of wildlife amid the climate crisis.

For example, some wildlife may experience the drying up of water sources, shifting tree distributions, higher temperatures, and less prey. This could drive them from their current home in search of more suitable environments and resources. Without connectivity, the displaced wildlife will struggle to adapt to these changes.

Freshwater, food, and communities need connectivity too

Lack of connectivity doesn’t just impact the movements of animals but also disrupts the important ecological processes that people depend on for healthy natural resources and a rich array of life for their livelihoods.

For example, dams disrupt free-flowing rivers and impact downstream communities by altering seasonal flows of water that carry sediments and nutrients. These are necessary for healthy floodplain agriculture and fisheries and help reduce the risks from floods and droughts. Deforestation for agriculture and other land uses and forest degradation, due largely to illegal logging, are fragmenting important forest habitats. This means that forests are no longer able to perform the functions that help maintain healthy ecosystems, such as providing food, mitigating carbon emissions, reducing soil erosion, and maintaining healthy waterways. In Latin America, for example, more than half of the jaguar’s original range has been lost due to deforestation, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure development, isolating jaguar populations into individual pockets of land. Lack of connectivity among these habitats makes it difficult for jaguars to breed and seek prey, which increases human-wildlife conflict as jaguars turn to hunting livestock for food.