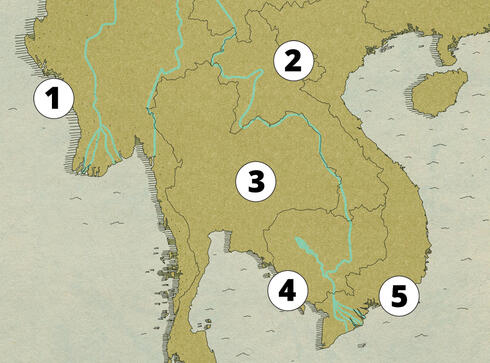

Mekong Flooded Forest

© HARRIET LEE-MERRION

The iconic reach of the lower Mekong known as the Mekong Flooded Forest is a rich mosaic of waterways, unusually deep pools, and forested island archipelagos. During the dry season, animals such as endangered hog deer forage in the forest. During the wet season, the forest floods, and fish take their place, feeding, breeding, and seeking refuge from predators in submerged stands of trees and shrubs. The forest is at the center of food security and survival for some 140,000 people, including Indigenous groups.

But in recent decades, it has come under pressure from unbridled development, overfishing, poaching, and other threats to its rich aquatic and terrestrial biodiversity.

WWF has been working here for almost 20 years to document the vital significance of this landscape and reduce pressure on the forest’s natural resources by helping communities to develop sustainable livelihoods. Recent initiatives include providing technical support to community fisheries and forestry groups; raising awareness, both nationally and globally, of the high biodiversity value of the area; funding river patrols in an effort to stamp out illegal activity and protect endangered species; and helping villagers develop ecotourism ventures.

WWF has also hired local people to protect the nesting sites of native birds. The project has proven successful in changing the behaviors of community members, who are now engaged in safeguarding nests rather than hunting birds or collecting eggs. In 2018, 105 villagers participated.

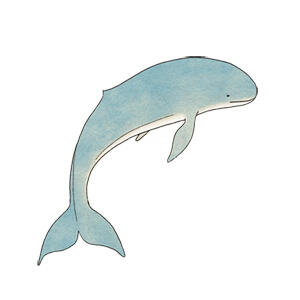

Also successful have been efforts to protect endangered Irrawaddy dolphins, whose survival is threatened by illegal electroshock and gillnet fishing. Day and night, rangers patrol the river, confiscating illegal gear and talking with fishers about the bounds of the law in the two wildlife sanctuaries—the Sambo and the Prasob—established here in 2018 with WWF’s help.

Today, nature enthusiasts flock from all over the world to wait patiently under bamboo umbrellas for the shy dolphins to pop up for air.

The controversial Don Sahong plant, which began operating in southern Laos in 2020, is the last lower Mekong barrier before the river becomes free flowing again as it continues into Cambodia. The Lower Sesan 2, Cambodia’s largest hydropower dam, is located on one of the longest Mekong tributaries. Approved in 2012 and operational by 2018, it displaced hundreds of Indigenous families and has already affected fisheries. A study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America estimated the dam would lead to a 9% drop in fish stocks across the basin.

Like its neighbors, Cambodia in recent years has struggled to meet its energy demands. Propelled by robust garment, construction, and (until the COVID-19 pandemic) tourism industries, its economy grew by 8% each year between 1998 and 2018. But though Cambodians pay four times the regional average cost for energy, almost 70% of grid users in the country face power shortages, and the nation must import nearly a quarter of its energy. For the Cambodian government, hydropower came to be seen as a cost-effective source of reliable electricity.

In 2016 Cambodian authorities announced plans to build not one, but two, massive hydropower plants—the Sambor and the Stung Treng—on the Mekong mainstem, smack-dab in the middle of the Mekong Flooded Forest.

An unprecedented threat

Not all hydropower projects are outright unsustainable; with careful planning, it is possible to choose a dam site that will result in lower environmental and social impacts. A 2019 WWF report estimated that with strategic and systematic planning, the potential loss of river connectivity from global hydropower expansion could be reduced by 90% globally—and more than 62,000 miles of river could remain connected. But the plans for the Sambor and Stung Treng power plants promised to drastically alter large stretches of the river.

If built, Sambor would become the largest dam on the Mekong and the farthest downstream. It would inundate 153,000 acres, displace some 20,000 people, and threaten food security for millions in Cambodia and Viet Nam. According to a Natural Heritage Institute (NHI) impact assessment, the dam “would create a barrier that would be devastating for the migratory fish stocks that move from the Tonlé Sap Great Lake to the spawning grounds upstream.”

As reservoirs associated with dams fragment rivers, converting entire stretches to lake-like conditions, not just the total catch of fish but the number of species dwindles. “Damming a river affects the life cycle of the fish, and while it takes some time, eventually species disappear,” says WWF’s Goichot.

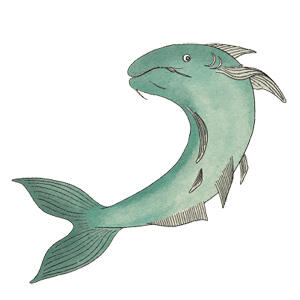

Some fish that travel long distances upstream to spawn, like the Mekong giant catfish—a fish that weighs as much as a grizzly bear—have already paid the price for hydropower development. Now critically endangered, the giant catfish has experienced a population drop to some 100 individuals.

And because dams trap nutrient-rich sediment that is needed to replenish downstream deltas, the Sambor “would also have a tremendous impact on the Mekong Delta in Viet Nam, which is the most productive delta in the world,” says Rafael Guavera Senga, WWF’s senior advisor for global energy policy. (See “Running Out of Sand,” below.)

The Sambor dam “would affect the whole economy of the river in a big way: fisheries, agriculture, and tourism,” says Senga.

Perhaps the most sobering prognosis for the proposed dams came from the NHI assessment. In its words, the dams would “literally kill the river.”

Irrawaddy river dolphin

Irrawaddy river dolphin

Asian elephant

Asian elephant

Red-headed vulture

Red-headed vulture

Giant freshwater stingray

Giant freshwater stingray

Tiger

Tiger

Mekong giant catfish

Mekong giant catfish