Heart of the River

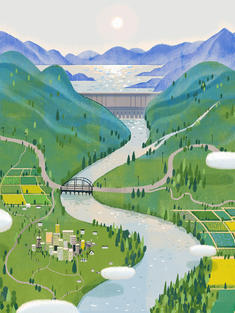

The most critical battleground for the Yangtze’s future is its middle stretch, where traditional economic development clashes with biodiversity in a battle for how China will manage its natural resources for the future.

“This is where agriculture and industry directly plunge their hands into nature,” says Jiang Yong, WWF-China’s acting director of biodiversity for the Yangtze Program. It is also where some of the last wild finless porpoises live.

Perhaps no place exemplifies the clash over natural resources here better than Dongting Lake, a vast lake in the flood basin of the Yangtze that is connected to, and fed by, the river at multiple points. The lake is a destination for tourists and a haven for millions of migratory birds. But the agriculture and dredging required to feed and house millions of people have reduced what was once China’s biggest lake to roughly a third of its original size.

It takes a lot of luck to meet a porpoise here these days, but the evidence of industry is everywhere: hundreds of colossal dredging vessels and barges—hulking masses of steel spitting out sand scraped from the bottom of both river and lake, pulling up lobsters, prawns, and vegetation as bycatch. Much of the sand mined here is shipped more than 600 miles down the muddy Yangtze to build booming cities like Shanghai. It goes into the concrete for skyscrapers, the glass for windows, and the asphalt for roads.

But sand is an essential part of the ecosystem on which the finless porpoise depends—and its removal upends that ecosystem entirely. The whirring and chomping of the sand-raking boats also interferes with the porpoises’ sonar, which the cetaceans use to navigate and hunt.

Zhang Xinqiao, manager of species protection for WWF-China, says the porpoises are completely disoriented by heavy boat traffic. “They get sensory overload from all the boats and become exhausted swimming back and forth to escape,” he explains. Confused and tired, they’re vulnerable to propeller blades.

Today, the government is making efforts to return parts of Dongting Lake to its preindustrial state. And as in many places, ecotourism is providing alternative livelihoods, with former fishers becoming restaurateurs, serving the lake’s tourists.

At a lakeside office, conservationists survey a swath designated for “sealed rehabilitation”—an essentially Chinese approach wherein whole areas are fenced off and relentlessly monitored and protected with as little outside influence as possible. The reserve’s staff members are responsible for stopping illegal activities—and for monitoring wildlife. Through powerful electronic telescopes, they survey the migratory bird population and jump for their camera phones at the sight of rare species including the white spoonbill, grey crane, and white-fronted goose.

Into all this activity, WWF injects a much-needed perspective, says Liu Song, Yangtze Program senior program officer. Pointing to the three massive bridges spanning the lake, he notes that the newest bridge, which is still under construction, was relocated based on WWF’s guidance, moving it away from sensitive wetlands to a location where it will do less damage to the ecosystem. He says that the growing, all-volunteer “dolphin monitoring” groups, which WWF fosters, helped the organization make the case.