It was nearly nine at night when a loud noise woke 24-year-old Sanju Pariyar and her family. An elephant was in their field and advancing quickly towards their house near Bardia National Park in western Nepal. A few minutes later, the wild animal had damaged the walls and roof of the Pariyar home, knocked down shelves in the kitchen, and scattered the family’s belongings in the darkness.

“It’s very natural to feel anger in the moment because we were sleeping and an elephant just came along and destroyed our house,” says Pariyar of the 2016 incident. Some of her neighbors experienced similar attacks on their homes, crops, and livestock from wildlife.

But Pariyar harbors little resentment towards the wild animals, and even champions their conservation. “If you take some time to think about it, perhaps it’s the responsibility of us villagers to know how to handle the issue and use the right techniques to scare away the animal.”

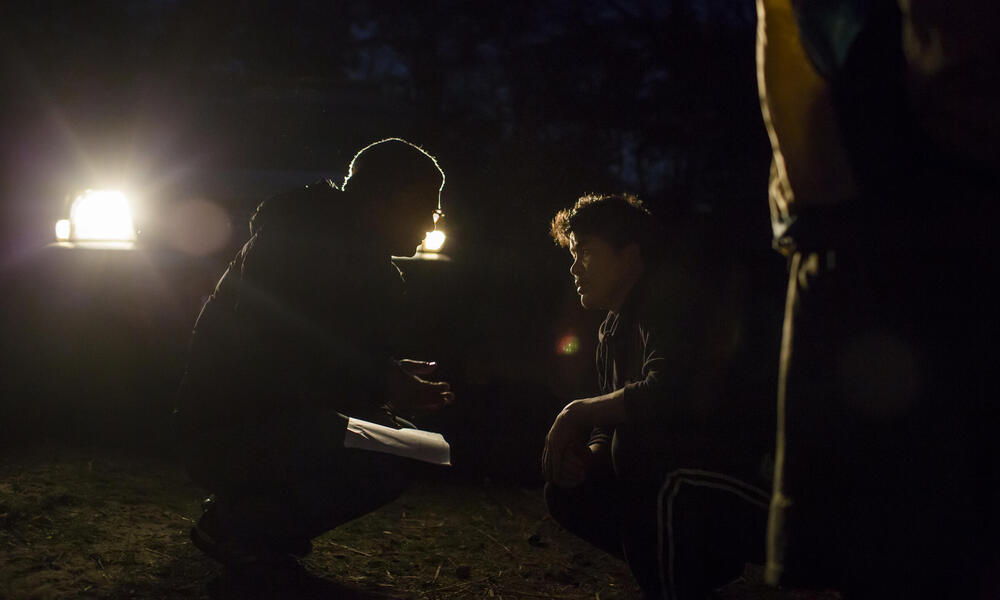

It’s that type of public awareness that Pariyar hopes to raise through her volunteer work as a member of the local Rapid Response Team (RRT). Established by WWF Nepal in 2016, RRTs help to engage communities in wildlife protection efforts, manage human-wildlife conflict, and monitor poaching and other illegal activities. Today, there are nearly 60 RRTs across Nepal.

As part of their work, RRT members offer fellow villagers’ advice on how to prevent and minimize the risk of attacks from elephants, tigers, leopards, and other wildlife that often live in close proximity to people. These include awareness programs related to park regulations, wildlife behavior, keeping safely away wildlife as well as preventive measures such as electric fences to keep out wildlife.

RRT members prepare people in case they should encounter unwelcome animals in their fields and homes. “You shouldn’t make noises from different directions as it might confuse the animal and make it even more aggressive,” explains Pariyar, who became part of her local RRT more than a year ago. “Instead, people should gather in one place and make noise from there” while providing a clear escape route for the animal.