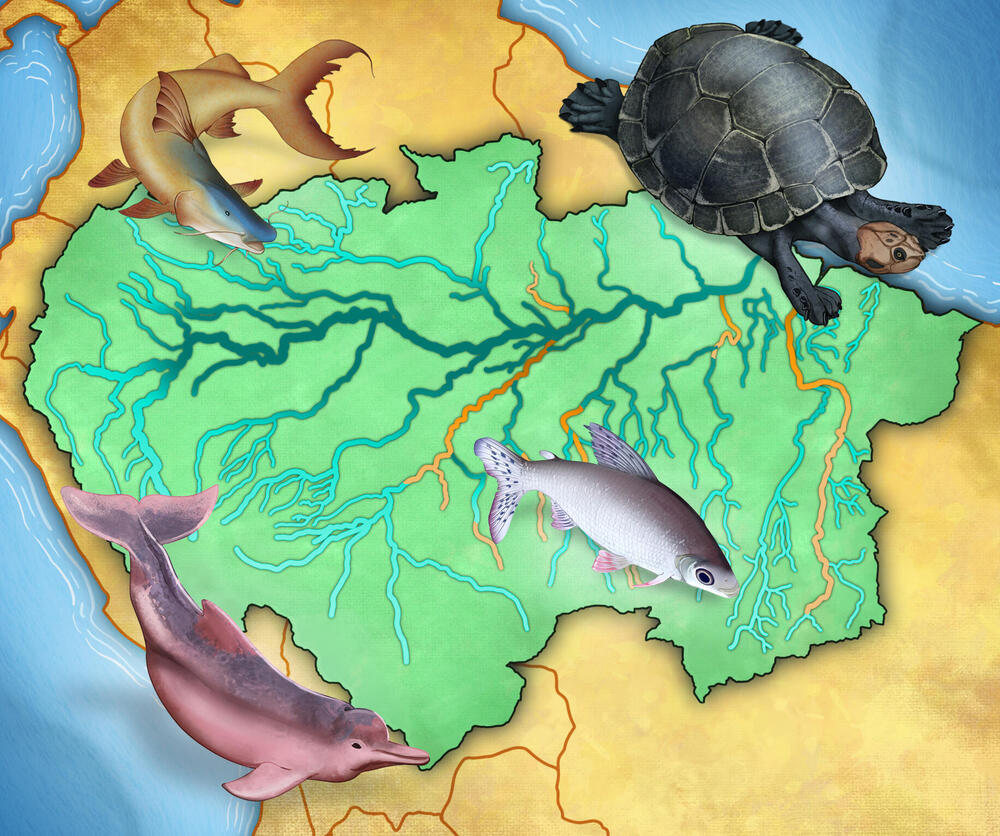

The Amazon River, one of the most iconic rivers in the world, is more than a single river running through the rain forest. It connects hundreds of rivers and streams (known as tributaries), vast floodplains, and wetlands that cover a wide swath of South America.

The vast network of rivers and associated wetlands within the Amazon basin allows for movement: of nutrients, of water, and of thousands of species. Like a central highway through a busy city, the Amazon river creates a migratory pathway for animals to find new sources of food, mating grounds, or safe spaces away from predators.

However, proposed dams on many of the Amazon’s tributaries would fragment this important network. The dams would block the movements of aquatic species, including migratory fish, turtles, and river dolphins. On tributaries where dams already exist, fish species that support local fisheries have declined, impacting livelihoods and food security in the region.

WWF, along with scientists from several organizations and academia¹, conducted a review of the use of more than 200,000 miles of Amazonian rivers by long-distance migratory fish and turtle species and river dolphins to develop a map of the most important routes or freshwater connectivity corridors, also known as swimways. By understanding which rivers are critical, decision-makers can take action to protect certain river stretches or otherwise plan for siting or designing infrastructure in alternative, more sustainable ways.

This model could be applied in other river basins around the world to better protect migratory freshwater species by mapping their swimways within river systems.

Without protecting their migratory pathways, we could lose some of the charismatic and unique species of the Amazon.