Inland Waters Finally Get the Mention They Deserve

- Date: 02 February 2023

- Author: Michele Thieme, Deputy Director, Freshwater

After last December’s Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD), just about every aspect of its successes and failures has been dissected and digested at length. But there are two little words from the conference that, weeks later, are still at the forefront of my mind because of the victory they represent. Those words are “inland waters.”

Finally, after years of hard work to raise the profile of inland waters or freshwaters¹ through advocacy with global governments and policymakers, 2022 saw the phrase “inland waters” prominently included in the text of the CBD’s resulting Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Let me explain why this is such a big deal to me and other freshwater conservationists. I’ve always had a soft spot for the underdog. Freshwater ecosystems and the species they hold– hidden from view and often slimy or drab in colors – can certainly be considered the underdogs of the conservation world. Even the most charismatic freshwater fish – think sturgeons and giant catfish or salmon – are often pictured hanging from a hook in their jaw – not the most flattering of poses. Out of view and out of mind, freshwater species are experiencing dramatic declines. It has often been discouraging to be among the few championing these forgotten treasures of the world’s freshwaters. Yet there is a dedicated group who have continued to beat the drum for river dolphins, freshwater fish, river otters, salamanders and frogs, mussels and clams, dragonflies and damselflies, crayfish and the millions of other inland water species.

Our WWF team refused to let freshwater ecosystems be forgotten, and we particularly focused on ensuring that inland waters were named explicitly in Targets 2 and 3 regarding restoration and protected and conserved areas respectively. Additionally, we had advocated for numeric restoration targets for wetlands (350 million ha) and rivers (300,000 km). In the end, inland waters were explicitly named in the text but numeric targets were not:

TARGET 2: Ensure that by 2030 at least 30 per cent of areas of degraded terrestrial, inland water, and coastal and marine ecosystems are under effective restoration….

TARGET 3: Ensure and enable that by 2030 at least 30 per cent of terrestrial, inland water, and of coastal and marine areas…are effectively conserved and managed through ecologically representative, well-connected and equitably governed systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, recognizing indigenous and traditional territories…recognizing and respecting the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities, including over their traditional territories.

But with that first step of having inland waters named, we believe there is still a window to ensure that the extent of restored inland waters is tracked over time through the selection of indicators.

Another key highlight is the explicit recognition and naming of indigenous and traditional territories. This is a major milestone toward indigenous and community-led conservation being given the acknowledgment it deserves, for the critical role that indigenous peoples and local communities play in restoring and stewarding lands and waters around the world.

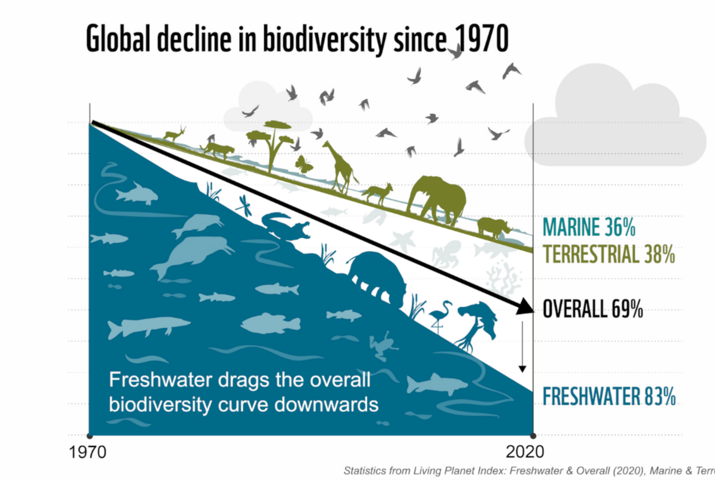

The inclusion of a few words might not seem all that revolutionary, but I assure you this is a major step toward solving our biodiversity crisis. Raising inland waters to be on par with terrestrial and marine realms provides an unprecedented opportunity for shifting the paradigm and seeing real progress on the protection and restoration of freshwater biodiversity. WWF’s Living Planet Index starkly illustrates how much freshwater species populations are pulling down the overall curve of abundance of species populations – with the implication being that freshwater populations must recover if we are to halt and reverse biodiversity decline overall.

Living Planet Index values from 1970- 2020 for terrestrial, marine and freshwater realms, and overall.

To make this happen on the ground, there is a need for significant increases in capacity, resources and attention to freshwater environments—something that is now explicitly recognized by having the targets above. Because of this I expect to see a much brighter spotlight on freshwater or inland water-focused topics by CBD COP16 in Turkey in 2024 and the upcoming UN Water Conference provides an opportunity to move commitments to action on these targets forward in the near term.

The text of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework provides a key milestone on the path towards restoration and protection of freshwater systems. We must now continue on this hard-wrought path and make sure that the funding, knowledge and capacity are secured to implement the targets as written.

One encouraging example of how these words are turning into action: the governments of Colombia, The Netherlands, Ecuador, Congo, Kazakhstan, Costa Rica, Mongolia, Mexico, and Gabon, along with representatives of the GEF and Ramsar Conventions, initiated discussion of a ‘Freshwater Challenge’ while together in Montreal. They have called for restoration and protection actions needed and integration of inland waters solidly into countries’ National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans.

Next up is the UN Water Conference in March. Countries, funders and the private sector must now follow through with concrete commitments of resources and actions to ensure that inland waters and the life within them don’t once again disappear beneath the surface.

¹Inland waters comprise all kinds of non-oceanic water bodies, or components thereof, on or adjacent to the land, including groundwater. They can be fresh, saline or brackish but, in practice, most inland waters are freshwater environments (see https://www.cbd.int/waters/inland-waters/). Accordingly, the term ‘inland water’ ecosystems is used and, hereafter, refer to the associated ‘freshwater biodiversity’ that they support