Farming for the Future of Tanzania

- Date: 20 July 2016

- Author: Casey Harrison, WWF

An aerial view of small farmers feilds being irrigated during the dry season in the Ruaha catchment, Tanzania.

Flying at 10,000 feet over Tanzania can give you a unique perspective on the country’s landscapes. On a recent flight over the Nguru Mountains, our pilot told us how he’d watched first-hand over the last 30 years as the region’s forests have retreated, soil has eroded, and rivers have grown murkier, all largely due to unfettered agricultural expansion. And that’s a big part of the reason my colleagues and I were there.

We were together in the Southern Highlands on a scoping journey for the CARE-WWF Alliance, learning from governmental, community, and agricultural leaders and identifying sustainable agricultural policies and practices that can conserve biodiversity and natural resources while creating jobs and food for vulnerable women and men.

Tanzania is a particularly important place for the Alliance, which combines CARE’s poverty-fighting, social justice mission with WWF’s focus on environmental conservation. According to the UN, Tanzania’s population will double within the next 35 years, growing at a rate that’s four times faster than the rest of the world. And while the country’s natural resources—particularly its water—are already stressed, climate change will only make things worse. This will not only endanger people, but it will also harm many glorious and valuable ecosystems, along with the rich species they support, including elephants, black rhinos, leopards, lions, and cheetahs.

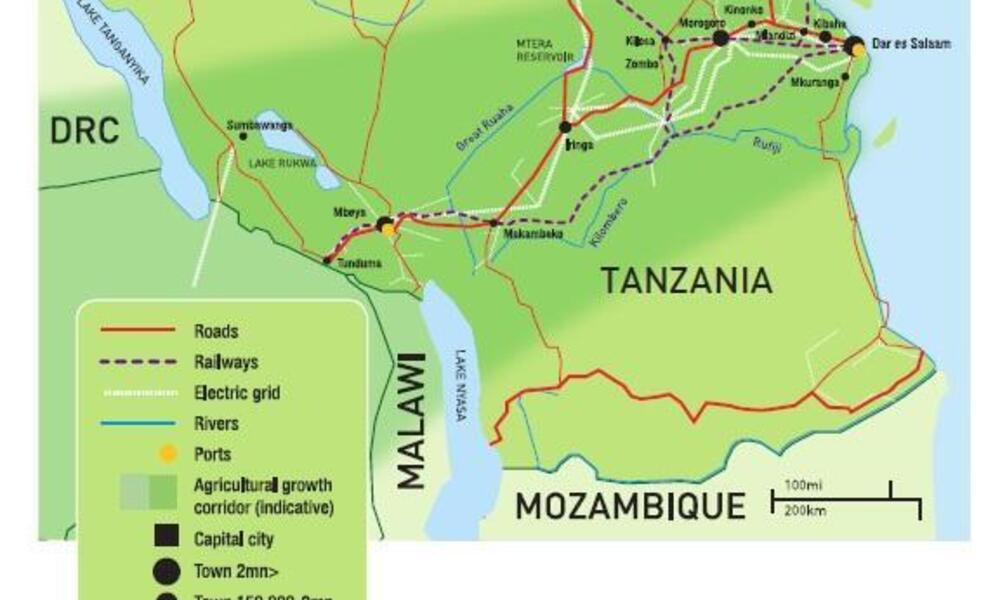

The Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania was created at the World Economic Forum Africa summit in 2010 with the support of farmers, food companies, and the Government of Tanzania. The program links farmers, agribusinesses, and related service providers to boost efficiency and enable collective action to reduce social and environmental impacts.

Our ultimate destination was the Usangu Plains, a threatened landscape surrounded by rolling hills at the headwaters of the Great Ruaha River. Located within the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT), the Plains have seen an increase in agricultural investments over the past decade. This has brought some economic growth to the landscape, but local conflicts over land and water are ongoing and communities continue to experience high levels of poverty. As a result, communities and wildlife remain threatened.

Tanzanian farmers and their livestock rely on the Great Ruaha River. As in Zambia, competing demands on water are stressing this precious resource.

Moronda B. Moronda, community outreach warden for the Ruaha National Park, told us that dwindling water resources, the expansion of inefficient irrigation, and increased soil erosion intensified seasonal droughts. Indeed, as we have seen here and elsewhere around the world, water scarcity creates a vicious cycle for marginalized communities. By limiting farmers’ yields, water shortages incentivize poaching, charcoal production, and agricultural expansion, which encroaches on forests, grasslands, and other habitats, promotes human-wildlife conflict, and strains water even further. And those are just the immediate effects. Over the long term, this feeds an even bigger vicious cycle: climate change.

As evoked in the UN Sustainable Development Goals, there are intimate links between human well-being, economic prosperity, and a healthy environment. Grace Macha, agricultural advisor to the regional commissioner of the Iringa region, passionately illustrated how those ties have been frayed in the Usangu landscape. She explained that a lack of coordination, insufficient extension services, and scarce freshwater resources in the rural areas of Iringa undermine sustainable development efforts. Defiantly, Macha remains committed to bringing sustainable agriculture and livelihoods to her region, but emphasizes that it’s only possible through coordinated efforts that assure market access, incentivize better agricultural practices, and enhance government extension services for smallholder farmers.

Throughout the wetlands of the Usangu landscape, smallholder farmers can generate profits on small plots by growing horticulture crops such as onions, but efficient irrigation and water governance must both be optimized to achieve sustainability. The Tanzanian Horticulture Association promotes techniques and technologies, such as drip irrigation, to use water more efficiently.

A promising and emerging crop in the highland areas of the Usangu landscape is soybean. Soybean production is expanding across southern and east Africa, and Tanzania is no exception. Currently, demand for soybean in Tanzania far outpaces domestic supply creating a reliance on international imports. This emerging soybean frontier will be critical to fighting poverty in Tanzania, but only if environmental, socioeconomic, and geopolitical risks are addressed through action and policy. In Iringa, we met with Seleman Kaoneka, program manager for the Clinton Development Initiative, and visited soybean demonstration plots under its Anchor Farm Project. They have reached over 4,000 smallholder farmers, but stressed that the Alliance can help expand their reach, establish new climate-smart practices, and enhance local extension services through partnerships.

There is still more for us to explore and understand, but this trip reinforced Grace’s point. It will take everyone working together to overcome these immense environmental, economic, and social challenges. It requires partnerships with SAGCOT, the private sector, government, and civil society—partnerships we’re building in the region. Through the application of proven strategies, the Alliance will work to reduce poverty for agricultural communities, return water flows to the Great Ruaha River, and increase climate change resilience for people and nature to thrive.

With support from the Clinton Development Initiative, soybean, sunflower, and corn farmers are adopting conservation farming practices that extend the life of the farm.

The CARE-WWF Alliance was founded in partnership with the Sall Family Foundation in 2008 and continues to thrive thanks to their longstanding support. Our joint work is also generously supported by USAID, several anonymous foundations and many others.