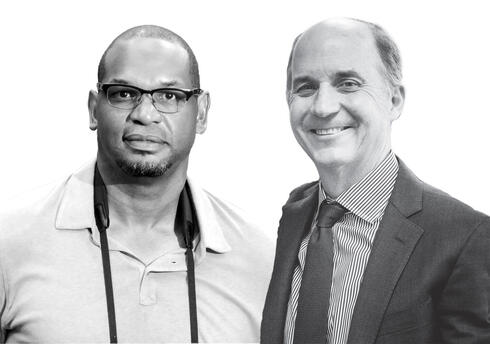

CARTER ROBERTS Drew, it’s a pleasure to have you with us. To begin with, we’re both from the South, land of some of the greatest writers in our country, and a land with a complex, fraught history. How has being southern influenced your affinity for nature and also your penchant for writing?

DREW LANHAM Thanks, Carter. It’s great to see you again. I was born in Georgia but grew up in South Carolina, on a family farm that probably came into ownership back in the early 1900s. My ancestors were likely enslaved on that land. So there’s this long tie to the land for us, first by chattel but then by choice.

It’s hard for me to go anywhere, whether it’s cotton fields or a rice marsh, and not think about those places as they were under cultivation and duress. But I also see what they are now in terms of conservation. That story is alive in me as a descendant of enslaved people—and as the descendant of free people who decided they were going to stay on the land, and work the land, and help the land work for them.

CR You and I talked about my kids being drawn to writing, not only because they love to write, but also as a way to wrestle with trauma we all face at some time in our lives. You’ve talked about the cultural dimensions of that. I think increasingly in the world of conservation, we’re dealing with trauma; both in a human sense and an ecological sense, the systems that we love are getting torn apart. And yet somehow a lot of the work we both do is about defining what makes a place meaningful and real, addressing ways in which that might be broken, and going through some process of reconciliation and restoration.

DL For me, the therapeutic aspect of nature writing is this confluence of past, present, and future. I think about my upbringing, about disappearing for hours between my grandmother’s house and my parents’ house on my daily ramble back and forth, and what that meant for me.

Being able to escape down to the creek, or wherever—I may as well have been in a wilderness 1,000 miles away. Being present in wildness is what drives me. Conservation is really an act of the heart and, for many of us, of remembering what nature did for us in the past. I’ve never seen nature as transactional. I’ll be honest, Carter, I really hate the phrase “ecosystem services.”

CR In that sense we must be kindred spirits. While economic arguments matter, I am definitely not in this business because of the economic value of nature. I am in it because of the wonder of nature and because it feeds my soul.

DL I know it’s important that trees breathe for us, that pollinators feed us, but those things can also reduce wildness to a commodity. I would hope that we’re able to barter into that economy some love and care and remembering—about what the ground that we stand on does for us, how it restores our souls first. To me, at the heart of conservation is simply doing better by nature because, for many of us, man, it saved us.

CR I’ll talk about the prose and the poetry of our work. We need the prose because if we’re going to convince a finance minister to allocate budget for a park system, we’ve got to be able to talk about what’s at stake economically. But the poetry—that’s what brings it all to life.

DL For me, poetry leads the way. There’s something that’s immediate about poetry, that grabs us in ways that—if we’re fortunate—can lead us toward language that becomes a policy or practice. This stuff takes a great deal of imagining. It’s a wonder and a privilege to do my work in a way that I hope contributes to something existing in abundance that was slipping off the edge.