Whale Shark Interaction Guidelines

Do not touch the whale shark

Do not touch or kick the corals

Do not take anything out of the sea

No fishing

Do not feed the fish

Do not use scuba and any motorized underwater propulsion

Do not throw trash

Do not undertake flash photography

Do not restrict movement of the whale shark

Maximum of six swimmers per shark

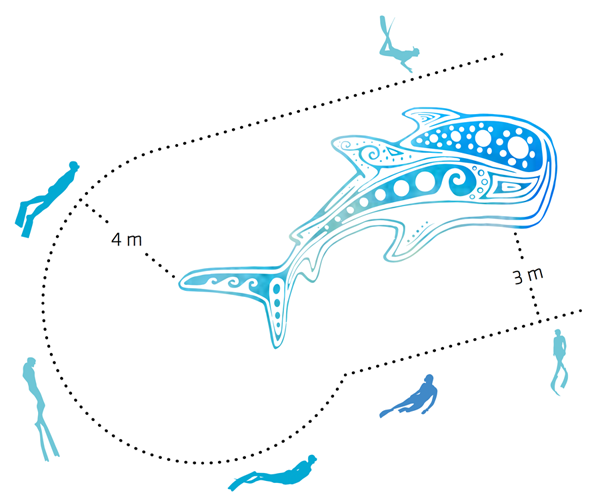

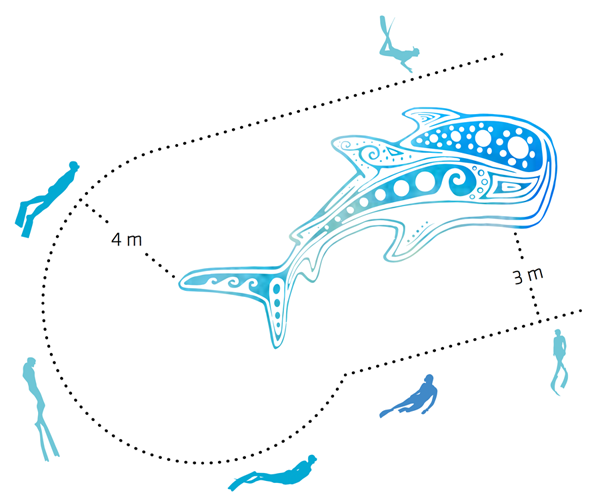

Stay a minimum distance of 9 feet from the shark at all times

In Donsol, whale shark interactions are carefully regulated; only 30 boats at a time, for a maximum of 3 hours. But despite the many rules in place (see above), the atmosphere is welcoming and convivial. Everyone is in this together, and the success of the system is a common source of pride. Alan tells me that people here recognize that “whale sharks are not only good for BIOs but also for the resorts, the shop owners, and the market vendors.” In Donsol, all but one of the resorts are owned by local families, as are the boats. “It’s good for us all,” Alan continues. “We have better transportation now. Better education.” Alan’s work as a BIO enabled him to send both daughters to college; one is studying to become a chemical engineer. Without the whale sharks and the reliable income generated by responsible, nature-driven tourism, he says, “maybe my daughters would stay at home, selling my fish.”

Twenty or so years ago, Alan was a tricycle, or pedicab, driver and a fisherman. Most people here were farmers and fishers, and the town was sleepy, without even a single road to bring visitors in.

Life changed in 1998 when a group of scuba divers arrived in Donsol to see if the anecdotes about frequent whale shark sightings were true. Their recreational dive turned into a rescue mission when they freed a whale shark stranded in a fish corral. The incident was reported to the WWF-Philippines office, kick-starting a nearly 20-year partnership with the government that has evolved from simply understanding the tourism potential of protecting whale sharks, to establishing systems for providing tourism services to visitors, to ongoing research that feeds into effective conservation planning and management.

Also in 1998, Donsol declared itself the country’s first municipal sanctuary for the butanding, in response to the threat of increasingly high demand for whale shark parts in Asian markets. That same year, the hunting and sale of whale sharks was banned throughout the Philippines.

Although there are regular sightings and interactions in places like Donsol, not much is known about the biology of the world’s largest fish. Whale sharks are elusive, transient foragers, on the move for an average of 14 to 16 miles each day, with populations appearing in the warm, circumtropical waters that hug the globe. Estimates say whale sharks may live to be 100 years old, producing offspring only after 25 or more years—a life span and maturation process that make them especially vulnerable to human interference. Globally, the species is assessed as endangered, with threats including habitat loss; marine pollution; vessel strikes; trade in the species’ flesh, liver oil, and fins; and irresponsible tourism.

As of 2016, WWF researchers had identified 469 individual whale sharks in Donsol Bay. Further, despite the research done on whale shark biology, habitat, and migratory routes, no breeding ground has ever been conclusively identified. So when the smallest juvenile ever recorded was found in Donsol Bay, the area gained even more prominence as one of potentially great importance to the species.

Talking to the people here reveals a key change in attitude toward the butanding over the past two decades, one that Donsol’s mayor, Josephine Alcantara-Cruz, makes clear: “Before, it was just one of those sea creatures. Fishermen would see them as a competitor. Now everything has changed, because now it is their partner in life.” Having once thought of the butanding as a tiresome if accidental destroyer of fishing nets, people here now understand that the big fish can offer benefits so great that they are variously described as a lifeline and the backbone of the economy. The butanding, the mayor says, are “like part of the family”—and as such, worthy of protection and love.

So we have to ask: Why do they come? And what will make them stay?